CRUD Actions: Modifying and Deleting Data

Holochain allows agents to mutate immutable data by publishing special delete and update actions to the DHT.

What you'll learn

- Why you can't delete or modify DHT data

- How to simulate mutability in an immutable database

- Addressing concerns about privacy and storage requirements

Why it matters

Immutable public data is a surprising feature of Holochain and many other distributed systems. It's important to understand the consequences in order to make informed design decisions that respect your users' privacy and storage space.

Public, immutable databases

Data in a Holochain app is immutable for a few reasons:

- Immutability of the source chain and DHT data means we can safely assume that data wasn't changed after being published.

- Immutability makes data syncing faster, simpler, and more reliable. Mutable distributed databases often require complex coordination protocols that reduce performance.

However, developers expect CRUD (create, read, update, delete) to be a basic feature of a database; it’s an important part of most apps. So how do we do it on Holochain?

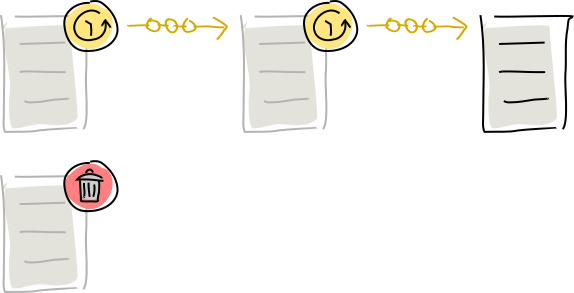

Simulating mutability

You might remember from a few pages back that we described each record as an ‘action’, not a thing. When you create, update, or delete a piece of data, you’re actually recording the act of doing it. (This is called event sourcing, if you’re interested.)

Here are all the mutation actions an agent can perform:

- A new-entry action calls an app or system entry into existence.

- Create creates a new entry.

- Update also creates a new entry, but marks an existing new-entry action as updated.

- Delete marks an existing new-entry action as dead.

- Create link creates a new link.

- Delete link marks an existing create-link action as dead.

- Redirect (not yet implemented) acts as a 'canonical' update, overriding all other updates and causing the old new-entry action's address to resolve to the new one.

- Withdraw action (not yet implemented) marks an existing action as dead, allowing an author to reverse a mistakenly published action.

- Purge entry (not yet implemented) directs a DHT authority to erase an entry from their store, which is useful for removing immoral content or honoring right-to-be-forgotten requests.

In every case where an action 'modifies' old data, it's simply sending a piece of metadata to be attached to the old data. The old data still exists; it just has a different status. The only exception is purge.

All the DHT does is accumulate all these actions and present them to the application. This gives you some versatility in deciding how to manage conflicting contributions from many agents. The only exception is redirect, which forces a canonical resolution of conflicting updates.

It's also important to note that an update or delete action doesn't operate on entries or links---it operates on the actions that called them into existence. That means you have to specify an action hash, not just an entry hash. In the case of deletes, an entry or link isn't dead until all the actions that created it are also dead. Again, purge is the only exception; it operates on entries.

This prevents clashes between identical entries written by different authors at different times, such as Alice and Bob both writing the message “hello”. That entry exists in one place in the DHT, but it will have two new-entry actions attached to it, each of which can be updated or deleted independently. Taking entry and action together, they can be considered two separate pieces of data.

Handling privacy concerns and storage constraints

You’ve seen how deletes and updates don’t actually remove data; they just add a piece of metadata that changes its status. Even with the future withdraw and purge actions, all they are is a polite request that other peers remove data from their stores. This can break users’ expectations. When you ask a central service to delete information you’d rather people not know, you’re trusting the service to wipe it out completely—or at least stop displaying it. When your data is shared publicly, however, you can’t control what other people do with it.

In a sense, this is true of anything you put on the internet. Even when a central database permanently deletes information, it can live on in caches, backups, screenshots, public archives, reading-list apps, and people’s memories. Holochain just makes it easier to share and persist data. Privacy is all about creating friction against data sharing, so your responsibility as a designer is to create appropriate levels of friction. Here are some guidelines:

- Be careful about what the DNA returns to the UI. Your zome functions serve as the API to the DHT’s data and can filter out old data. This doesn’t completely prevent people from accessing it, but it does force them to work against the system.

- Design your UI to communicate the permanence of the information users publish so they can make responsible decisions about what they choose to share.

Because data takes up space even when it’s no longer live, be judicious about what you commit to the source chain and the DHT.

- For large objects that have a short life, consider storing data outside of the DHT in separate, short-lived DHTs, IPFS, Dat, a data store on the user’s machine outside of Holochain, or even a centralized service.

- If an entry might have many small updates to it, queue them up and write them in one update. Or ignore the built-in update feature and commit updates as diffs instead.

- For large entries with frequent but small changes, break the content into ‘chunks’ that align with natural content boundaries such as paragraphs in text, regions in images, or scenes in videos.

Key takeaways

- All data in the source chain and DHT is immutable once it’s written. Nothing is ever deleted.

- It’s useful to be able to modify data, so Holochain offers delete and update actions that add metadata to existing data to change its status.

- Because this may surprise users, developers have a responsibility to inform them of the permanence of data and protect them from negative consequences.

- In the future we intend to introduce actions that request the actual deletion of data, as well as canonical redirects.